“Those who don’t learn history are doomed to repeat it.”

You heard that in high school social studies, too, right? I know; it didn’t exactly inspire me, either.

I don’t consider myself a historian, but I really want to make history, to leave the world a better place than I found it. As a person of faith, I want to be part of a revival and awakening movement—a historic outpouring of God’s presence, grace, and favor that changes a generation. Revivals and awakenings (names I’ll use interchangeably) draw new people to God, are often accompanied by the supernatural, and historically re-energize a once cold and stale faith.

These are not myths of days gone by. Revivals are certifiable, documented historical events—and they happen with pretty stunning regularity.

Dr. Michael McClymond, a professor of modern Christianity at St. Louis University, is one of the world’s foremost experts on revival movements. According to his years of research (and a 1,200-page, two-volume encyclopedia he wrote on them), revivals happen every 50 years or so.1

Another historian, the late William G. McLoughlin, wrote, “Awakenings begin in periods of cultural distortion and grave personal stress, when we lose faith in the legitimacy of our norms, the viability of our institutions, and the authority of our leaders in church and state.”2

Cultural upheaval? Personal stress? Lost faith in the norms of church and state? I don’t know about you, but when I look at my news app, I find all that before I even swipe once.

Maybe my history teacher was right after all. Perhaps those who do learn their history will be the most prepared when the next great movement of God sweeps our nation. Now that I can get behind.

Below are five of the biggest, most impactful revival movements in the history of America—and what they can teach us about the next generation-defining move of God. It could be just around the corner.

5 Revival Movements To Get Us Ready for the Next One

1. THE FIRST GREAT AWAKENING (1734-1743)

Like America? A revival movement helped kickstart that.

In the early 1700s, the colonies were going through severe growing pains. Far from the religious devotion of the original Pilgrims, church membership had tanked. But God wasn’t finished. Touches of awakenings were beginning to pop up sporadically on the map, and things hit a fever pitch when one of the greatest preachers in England, a young man named George Whitfield, came to America.

Unlike the monotone preachers of the day, Whitfield was a performer. He was dramatic and commanding, with a booming voice said to reach 15,000 people without amplification.

Breaking with tradition, Whitfield held meetings outside, in the open air. Huge crowds gathered and hung on his every word. It offended many of the traditional preachers of the day, but it worked. It is estimated that four out of every five American colonists personally heard Whitfield preach. During the Awakening, church attendance swelled from 14% to 55%.

The gift of the First Great Awakening was an understanding that God wasn’t a disapproving father looking for an opportunity to punish His children (which is how it felt to serve this guy) but a merciful, pursuing, personal God.

Speaking in 1818, the 2nd president of the United States, John Adams, said:

“The revolution was effected before the war commenced. The revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people; a change in their religious sentiments… was the real American revolution.”3

By the time the First Great Awakening died down, historians believe 20,000 to 50,000 people were added to churches in New England.

Whitfield and other preachers who followed his model were effective because they differed. They broke with tradition. They took the good news of Jesus into places it hadn’t been preached before and proclaimed it in a way that caught people’s attention. The religious types judged them for it, but thousands upon thousands of lives were changed.

When the next great awakening comes, it will likely reach the masses through methods that feel different, dangerous, and maybe even a little sacrilegious.

2. CANE RIDGE (1801) AND THE 2ND GREAT AWAKENING (1824-1840)

By the 1800s, church attendance had plummeted again, with only 6% of America’s population belonging to one. The rise of the Enlightenment, with its emphasis on science and reason, led to widespread questioning of faith. It was time for revival again.

In August 1801, a minister named Barton Stone, living in the wilderness of Kentucky, prepared for a communion service at Cane Ridge. As his parishioners came to take part, the Spirit of God fell upon the people in unexpected ways. Some would shake, others fell to the ground, and still others preached or sang. Word spread and people came from miles around to join in—or at least watch from the sidelines.

By the time the revival peaked, 20,000 people had come to this rural community. As you approached, it’s said the sound rivaled that of Niagara Falls.

While the revival only lasted a week, historians see it as the start of the Second Great Awakening, a movement that peaked with Charles Finney. Despite looking more like a pirate than a preacher, Finney took the lessons from rural Cane Ridge—and brought them to the heart of America’s greatest cities: Philadelphia, Boston, and New York.

Historians estimate that as many as 500,000 people came to faith through Finney’s urban gatherings. Emphasizing our potential to do good in the world, Finny was an early advocate of the abolitionist movement against slavery, and many of his converts joined in that work.

By the mid-1800s, America’s population had increased fourfold, but church attendance surpassed it, growing 10x over the same time period—all while simultaneously laying the tracks that would eventually lead to the end of slavery.

A transcendent encounter with God can happen anywhere, from rural churches to urban gatherings. They won’t just change us spiritually—you can expect them to upend the way we live. In that way, the impact of awakenings is felt far beyond the people in attendance. They’re not just for the faithful but for the world at large, impacting the way we live among, interact with, and love others.

3. THE BUSINESSMEN’S REVIVAL (1857-58)

In the years just before the Civil War, a man named Jeremiah Lanphier was living in New York City. A businessman by trade, his heart burned for the people around him. The future of the country was uncertain, with stress and anxiety accepted as a way of life. Bank crises were common, labor disputes were in the headlines, and corruption was widespread. People felt depressed, hopeless, and alone.

Unsure of how to help, Jeremiah earnestly prayed, “Lord, what would you have me do?” Working with a local church, he started weekly prayer meetings during the lunch hour: no preaching, no music, just a quiet space to pray together.

He opened the doors for the first meeting…and sat alone, wondering if anyone would come. By the end of the hour, six people had trickled in. The following week, it had grown to 20. The next week, 40. From there, it shot off like a rocket. It became so popular the prayer meetings moved from weekly to daily. With the original location bursting at the seams, other local churches began to host lunch hour prayer at the same time.

The meetings continued to grow, eventually spilling out of New York and springing up all around the country—with revival breaking out alongside it. Sometimes called The Great Prayer Meeting Revival, historians estimate that as many as 1 million people swelled into American churches, all prompted by the desire of one businessman to see hope and peace come to his peers.

Lanphier prayed a simple prayer and then took action. All awakenings are born from simple, radical obedience to God—even, as it did for Jeremiah’s first prayer meeting, when it seems unsuccessful at the start.

4. AZUSA STREET REVIVAL (1906)

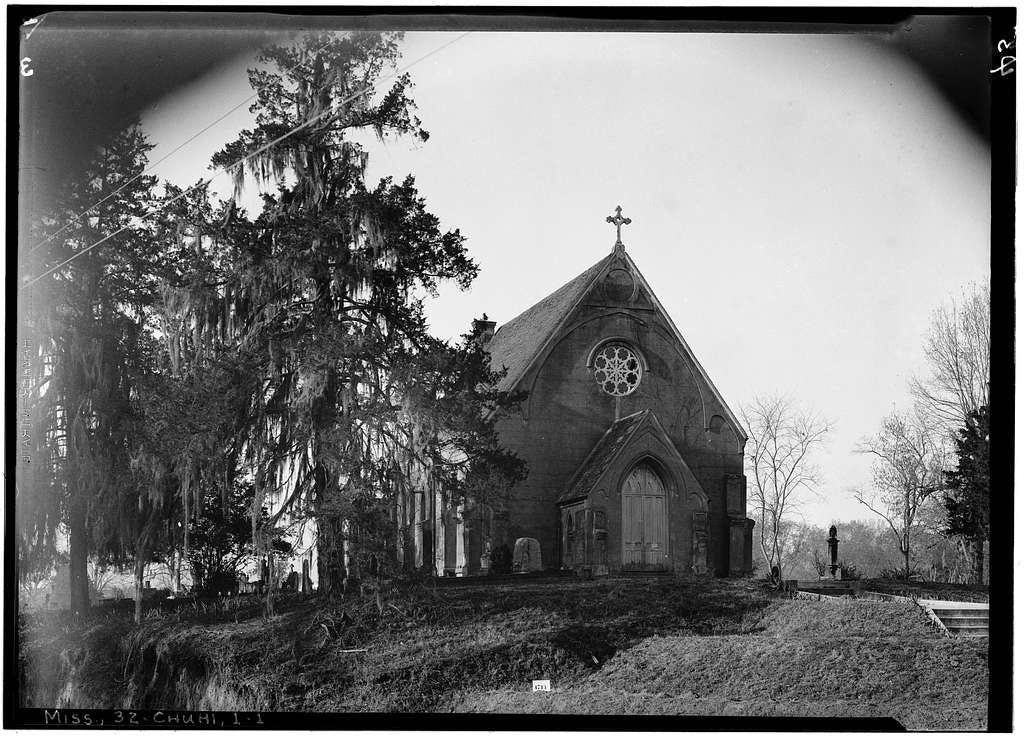

In the first years of the 20th century, an African-American pastor named William Seymour traveled from Mississippi to Los Angeles, hoping to get a job at a local church. They rejected him, but undeterred, he started prayer meetings in a nearby house. Born at the end of the slave era and living during Jim Crow, Seymour routinely experienced racism, even among other Christians. Known for his humility and commitment to prayer, he would spend hours each day seeking God on his knees. Things began to change when he invited others to join him.

Daily prayer meetings started in a house, but when attendees swelled, they moved into a dilapidated building on Azusa Street. For the next three years, people gathered there daily to pray together, and many had supernatural and spiritual experiences—including healings, speaking in other languages, intense emotional outpourings, singing, and shaking.

It was a ramshackle place, with people sitting on old benches, crates, and barrels. Yet historians believe anywhere from 300 to 1,500 people would cram into this building on Azusa Street daily, a mixed crowd of all races, which only intensified much of the racism that Seymour was experiencing. It grew to such a pitch that it made the front page of the LA Times.

After three years of daily prayer, the meetings began to die down. But not before hundreds of thousands of people came face-to-face with a powerful God that stooped down into their daily lives. Hundreds of missionaries also went out of the Azusa Street Revival. Known as the “missionaries of the one-way ticket,” they flew off to far-flung countries across the globe without a plan to return. Their goal? To introduce others to the God they had met on Azusa Street.

While there are certainly things we can do to encourage or quell the movement of God, awakenings all begin with prayer—an honest seeking of God. And they all come with a price to pay. Seymour was harassed, disparaged, and publicly spoken out against—and not just by people outside the faith. But he continued anyway, practicing the humble and ardent faith of all the spiritual greats who came before him.

5. STUDENTS AND THE JESUS MOVEMENT (1948-70)

As the wars of the late 20th century raged, from WW2 to Vietnam, young people watched a steady stream of their friends and colleagues sent off to war—many never to return. A spiritual awakening was ripe for blossoming.

In 1941, a young seminary student named Jim Rayburn started YoungLife, doing things that had never been done—like establishing summer camps and busing kids from all over the country to attend—in order to reach teenagers with the hope of Christ. A decade later, Bill Bright started Campus Crusade for Christ with a similar intent to reach college students, using methods considered revolutionary for the time.

Around the same time, a young preacher named Billy Graham started holding crusades, eventually filling football stadiums with people eager to hear his message. Graham became one of the most influential evangelists of all time—holding more than 400 crusades, simulcasts, and rallies in 185 countries worldwide—with 215 million people in cumulative attendance.

Targeting people that traditional churches of the time were disavowing—hippies, stoners, and the counterculture—the Jesus Movement was the culmination of the Vietnam-era revivals. Born from and primarily targeting young people, the Jesus Movement gained traction around the globe after 80,000 young people attended an event organized by Campus Crusade for Christ held at the Cotton Bowl Stadium in Dallas.

When the Awakening comes, expect young people to be on the front lines—even (or especially) the ones who don’t talk, think, dress, or act like you do.

WHEN THE AWAKENING COMES…

Will we recognize it? Will we join in? Will we fan the flames? Or will we complain because it’s too loud, messy, inconvenient, weird, or young?

The next awakening will likely use new methods, like Whitfield, that might make us uncomfortable. The next revival movement won’t be marked by location but by people who, like Charles Finney, move their faith from their hearts into their hands. Awakenings are born from simple obedience and a commitment to prayer. There will undoubtedly be a price to pay, as leaders like William Seymour saw their names dragged through the mud. But the resilient and bold—the young and the young-at-heart—will likely find themselves among its earliest adopters, adherents, and evangelists.

We are overdue for the next great awakening movement in American history. Perhaps God is simply waiting for us to echo the prayer of Jeremiah Lanphier: “Lord, what would you have me do?”

The question is, are we bold enough to pray that prayer and then get our hands dirty? The most remarkable thing might be waiting on the other side.

“If my people, which are called by my name (the young and old), shall humble themselves (being willing to suffer like Seymour) and pray (with simple obedience like Lanphier), and seek my face (with boldness like Whitfield), and turn from their wicked ways (like Finney and his followers); then will I hear from heaven, and will forgive their sin, and will heal their land. (2 Chronicles 7:14 - parenthetical notes by the author.)

To learn more about revival and spiritual awakening, check out this page we made for you.

1Tome, Brian and Michael McClymond. “We’re Overdue for a Spiritual Awakening, So How Do We Get There?.” The Aggressive Life with Brian Tome podcast, 2024.

2McLoughlin, William. “Revivals, Awakenings and Reforms.” The University of Chicago Press, 1980.

3Rossiter, Clinton. “The First American Revolution.” Harvest Books, 1956.

Disclaimer: This article is 100% human-generated.

Reflections to share? Got an idea for an article? Email us at articles@crossroads.net

At Crossroads, we major on the majors and minor on the minors. We welcome a diverse community of people who all agree that Jesus is Lord and Savior, even if they view minor theological and faith topics in different ways based on their unique experiences. Our various authors embody that principle, and we approach you, our reader, in the same fashion. You don’t have to agree with every detail of any article you see here to be part of this community or pursue faith. Chances are even our whole staff doesn’t even agree with every detail of what you just read. We are okay with that tension. And we think God is okay with that, too. The foundation of everything we do is a conviction that the Bible is true and that accepting Jesus is who he said he is leads to a healthy life of purpose and adventure—and eternal life with God.